Note: this is part of my objective and carefully-researched opening take on the 2024 UK General Election contest.

As always, there’s a clutter of parties who’ll be hoping to make gains, but who have no hope of really shaping overall outcomes. Some of these, I’ll get out of the way immediately: the various factions in Northern Ireland and Plaid Cymru.

These are regional parties contesting too few seats to ever be a major factor, each with very limited individual support. This election is a contest between two ideas: the Tories are awful and must be removed no matter what, versus Labour will summon an Eldritch God with whom they’ll make an open-borders pact and the country will be flooded with immigrant Shoggoths. There is no room for a repeat of the DUP shakedown of 2017. In fact, even with the paucity of seats at play in these regions, it looks very unlikely there’ll be much in the way of movement from the current electoral map.

But there are two parties that fall into the Everyone Else category that it’s worth giving a bit more time: the Greens and the Scottish National Party.

The Green Party

The Greens have a PR problem. Some of this is ideological, some of it is not.

First off, those which are not are largely self-inflicted. There are a few to choose from, but I don’t think any is clearer than one I can easily show you: their policy position. Or, rather, how they’ve chosen to present it. See that massive sidebar on the left of the screen, with all the links? Click on one. At random. I did. I picked “Economy.”

Done it? Good. Now, did you just think “well, I’m not reading all that“? Me too. And I’m a politics nerd. What we’re seeing here is symptomatic of precisely half the problem the Greens have created for themselves; nobody who isn’t really eager to understand their policies will ever bother to read them. Those who are really eager to understand their policies are probably already invested enough that they’re voting Green anyway. They probably helped write them, even. Someone must have.

The Green Party Manifesto, Vol. 1

It’s a spectacular failure at Communications 101. I’m all for nuanced and well-considered policy positions, backed by evidence and framed by compelling arguments. But to win an election, you need to provide an accessible BBC Bitesize version that people can easily absorb.

This problem extends to the public face of the party. Did you know they have two party leaders? Many people don’t. Can you name either of them? I certainly couldn’t without looking it up, and I love politics. They’re Carla Denyer and Adrian Ramsay. For what it’s worth, Denyer looks as surprised by this as anyone.

And, like much of what the Greens do, that isn’t a bad setup. Different, but with potential upsides. It’s just a huge issue that most people don’t know that is the setup, much less who either of the people in question are. It’s a problem with messaging, which you really don’t want when your entire purpose is to get people to buy into your message.

But this is only half of their problem. The flip side is, they’ve grown up around a few activist factions with single-issue bugbears that are enormously unpopular with the majority of the electorate and, frequently, reality itself. It’s these that tend to get the headlines, because they’re easy to articulate and evoke a clear response. No nuclear power is probably the flagship of this armada of ideas that are neither popular nor sensible.

I won’t go into the rest in detail here (because I really am not reading all that), but the point is this: they’re a very long way from making a meaningful impact on British politics. They strike me as not so much a serious political party as a kind of alumni association for people who really miss being on Student Union action committees. But then maybe I’m doing them a disservice and all I need to do is read their 40-billion word Philosophical Basis.

Yet, despite all that, the Greens have more than doubled their predicted vote share – from 2.8% to somewhere north of 6%. Depending on how thinly spread that is, they could do anything from lose their one existing seat, to increase that count to 4. In the latter scenario, where they do that might have a small impact on major party totals, but mostly it’ll be a bit of a litmus test as to whether the appetite for shaking up the status quo is growing as much on the progressive side of things as it is on the far right.

Based on the polls – and the fact they’re not gaining votes because of a super-slick comms team – I’d say it looks like this may be the case. But how well they do nationally will confirm or deny that theory.

The Scottish National Party

Of substantially more importance than the Green, the SNP are – on paper – major players in a substantial number of seats. They currently hold 48 out of the 59 Scottish Westminster constituencies.

However, the party has recently undergone what we’ll charitably position as an ‘air-to-ground reshuffle’. Humza Yousaf terminated the SNP’s pact with the Scottish Greens, causing the Scottish government to fall apart, with him losing a confidence vote and promptly resigning.

This means the new leader, John Swinney, has only been in position for three weeks. The only headline of note that this has garnered is that he hasn’t bothered to fill the party function of Minister for Independence. It is very hard to interpret this as anything other than giving up on the idea of another referendum in the foreseeable future.

If we’re being honest, they’re probably pretty done-for, as Nicola Sturgeon was the very successful glue that held them together. Now she has gone and her replacement has turned out to be a hapless buffoon, and his replacement has just been released from the Party Leadership Womb, I suspect they’re going to suffer.

Sturgeon carried them through the (failed) independence vote of 2014, rode the wave of anti-Brexit outrage, and had the force of personality to act like a Westminster power-player without actually being one. Without her – and their raison d’etre of endless independence votes – I think what we’re seeing is more than just bad polls; I think they’re going to try and reinvent themselves as a broader political mission, then fall apart.

Whatever the truth, the relevant facts are that:

- Their polling was pretty bad even before the latest mess.

- Having a brand new leader installed 2 months before election day is far from ideal.

- They’ve functionally abandoned their core defining policy goal.

It’d make sense that things are likely to get worse before they get better, as now there’s an opportunity for people to voice their disgust in the form of the ballot box.

Which – like many other things mentioned in these posts – is bad news for the Tories. Nobody likes them in England and even fewer people like them in Scotland. But so long as those people who’d never vote Tory were instead voting SNP, it wasn’t that much of an issue. If they now – as is likely – end up voting Labour, that in itself is a substantial haul of extra Westminster seats that the Tories can’t win, nor can be hived off by Reform.

This might be a longer-term issue for the Conservatives, as if the SNP have in fact ditched their commitment to Scottish independence, they don’t really stand for anything that another party can’t also stand for. That translates pretty directly into “there’s no reason to vote SNP instead of Labour anymore” and the upcoming election will show us how many people have realised that. My bet? A lot.

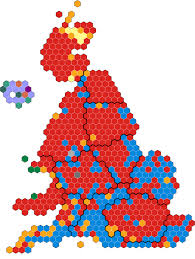

If that happens, we get a map that looks a lot like this:

And if this looks familiar, that’s because it’s the 1997 results map. There are some very slight changes (e.g. there are 650 constituencies now, rather than 630), but it’s near enough.

So, the SNP aren’t playing a part in the way that the Lib Dems and Reform will, by taking votes. They aren’t acting as a kind of yardstick for drift from the major parties, like the Greens will. They’re simply going to tell us whether Labour can start relying on Scottish seats again, which is doubtless something Starmer’s team will be keen to understand. Not least because it helps them gauge their odds of winning a second term in another 5 years, which in turn helps set policy direction and scope.

Just before I leave off here, you may note that I haven’t linked to the SNP policy platform. That’s because it isn’t really relevant to this election; most of the country can’t vote for them and they’ve traditionally been a one-issue party, but have now seemingly dropped that one issue. You can read their positions here if it interests you – just be aware that there is effectively nothing in there that will influence the big picture.

One thought on “2024 Election Preview – Everyone Else”